A Word on Problem 1 – Transcript

Key Moments

1:00: How to Read Problem #1

3:42: The Diagram in Problem #1

6:01: Scoring

9:32: Clarifications; 13:50 Clarifications

10:08: Program Guide

12:10: Forming a Team

15:11: Key Rules for Problem #1

18:50: Boundary Lines

21:10: Character and Human Character

22:44: Effectiveness

24:31: Myths about Problem #1

26:20: Propulsion and Steering

Video Transcript:

Welcome to the Problem 1 specific training video. I am Bruce Mackinlay. I am the Assistant Problem Captain for Problem #1.

Problem #1 is a technical problem that involves a team-created vehicle. As a technical problem, there are specific elements that are somewhat unique. In this video, I’ll try to present these unique elements.

There are four parts to this video. The first part is the discussion about how to read the Problem Description. This will not replace the more general training on how to read a problem. I plan to focus on things that are important for Problem #1.

The second part is to review the program guide. Again, I will focus on issues related to Problem #1. The third part of the video is some advice for coaches on Problem #1. And finally, I will try to give you some insight in how to present Problem #1 as a video in a Virtual Tournament.

This video will be fairly specific and detailed. You may want to pause it or replay it.

1:00: How to Read Problem #1

Let me start with how to read Problem #1. Here’s the Problem Synopsis for 2017. It states that your team will design, build, and run vehicles from a multilevel parking garage. The Problem does not really define a multilevel parking garage, but I hope it’s clear that we’re not talking about a large vehicle.

Here’s the Problem Synopsis for 2019. It states that you need to assemble and ride on the vehicle. If you can ride on it, then it can’t be really small.

The point is in some years, the Problem is what we call a Small Vehicle Problem. In other years, it’s a ride-on or a Large Vehicle Problem. This difference tends to color the whole development of the solution.

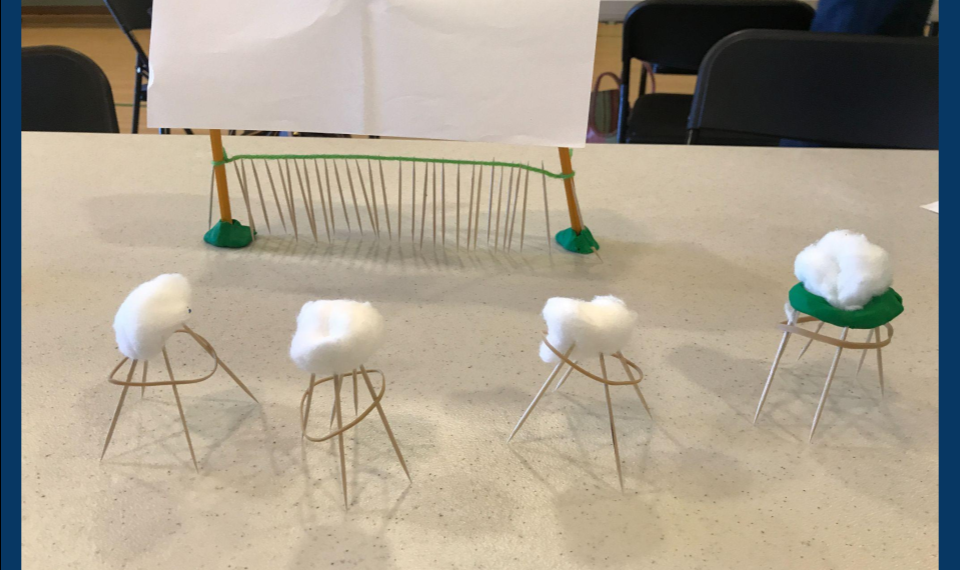

Here’s a typical start of a competition. The team is waiting for the announcer to complete the introduction and tell them to start. Once they do the team will bring their vehicle out from the staging area. Notice there’s nothing on the competition floor other than some taped lines.

In 2016, the vehicle was placed on the competition floor. When the team started competition, you would see the vehicle out there was inside of a taped box. The point is, don’t assume the vehicle will be with the team in the staging area at start time.

In 2019, the instruction was to have the vehicle in one or two suitcases at start time, then move it out behind a line on the competition floor. Since it did not say to place it in a specific location, just in a suitcase, then this would mean that the suitcase containing the vehicle would be with team in the staging area. Teams tended to get confused and place the suitcase out on the competition floor behind the line.

2:55: Non-technical items

Another element in Problem #1 is there’s always something extra that does not have to do directly with the vehicle. In 2020, we had two characters, one, a human character called the Long Shot character. And second, another pair of characters who did not take the Long Shot character seriously.

Finally, there was something, a celebration of the end, that the characters had to perform. Problem #1 teams sometimes treat these as second thoughts and fail to have them integrated effectively in the performance. As a team, how are you going to make sure all specifications of performance are completed?

3:42: The Diagram

The next item I want to discuss is the diagram. In Problem #1 there is always a diagram for how the competition is space is laid out. Every year this is different. There are conventions for how the diagram is presented that the team may not know.

Let me use the example from the 2020 Problem description. In this diagram, there are solid lines and dotted lines. The solid lines are where we place painters’ tape on the ground in the competition site. People get confused about the dotted lines. The dotted lines are dimensional lines. In other words, they’re there to help us know how far things are apart. In this diagram, the leftmost box is five feet from the center box.

We do not place tape on the ground where there are doted lines. Also, the dotted lines do not tell anyone how or where your vehicle must travel. They don’t say anything except how far apart things are.

Finally, when we set up the competition floor, we try to draw lines and boxes on the ground using painters’ tape exactly as shown in the diagram. Later, I’ll go over boundary lines in areas when we go over the glossary in the Program Guide. But this guide and the definitions in the Problem description drives how the tape will be placed. If you are unclear on where the painters’ tape will be placed, then contact your Regional Problem Captain for Problem #1.

Also at the bottom of the diagram is preferred audience seating. We will try to place the audience in this orientation where we can. In a specific Region or Division, the size of the room may not permit this layout. If it’s important to your team, please contact your Regional Problem Captain for Problem #1 to find out your audience’s location.

Make sure your team understands the layout. Find a space, use blue painters’ tape to draw it out on the ground. Have the team work out where the audience sits, and practice in it if you can.

Another area of confusion is that the judges do not sit in one location but try to stand around the site so they can see from more than one angle. The team should not direct their performance in a judge’s direction.

6:01: Scoring

The next thing I want to go over is scoring. Here is an example from 2019. When scoring a section, when it says two to five, for example, we call these subjective scored elements. Subjective scored elements are ranged from a low value to a high value.

Ask a team to pretend that they are the judges, and ask them, if you were scoring 20 teams, would you give all the teams the highest subjective score, the lowest objective score or something in between?

When it says zero or five, for example, these are objective scores. The team will only get zero or five, nothing in between. They are objective because the judge is trying to check if an event happened, nothing more. If it happens, then the team gets the full points. If none of the judges see it, then the team will get zero. Scores can only be the highest or lowest value.

What does it say about the impact of the total scores?

One key skill a team needs to learn is one of gamesmanship. This means that the team should look the total number of objective items compared to the subjective items compared to the total points and ask themselves, “Is this important to win every objective versus every subjective item? Where should we focus our effort and creativity?”

The scoring is different each year. So, it’s a judgment the team must learn to make each year and will be made differently.

Moving on to the penalty section. Often in Problem #1, in the penalty section, there are penalties unique to Problem #1. Here are the penalties for 2019. Notice there are two penalties specific for the year for this Problem #1: Penalty 6 and Penalty 7. This happens almost every year, but the penalties are different every year.

Make sure the team reads and understands these penalties.

In 2019, there were two penalties. Notice that number 6 zeros out the score for specific scoring elements. D7b means section D subsection 7, item b. Penalty 7 has a rubric for how the penalty disappoints are applied overall.

In italics there at the bottom is a general statement. And that is important for Problem #1. And I quote, “Teams that do not present a scored element of the problem will not receive a penalty, they will receive zero score for that category.”

What does that mean? For Problem #1, it generally means either a team ran out of time and failed to completely do one leg of the Problem, or they had some element of mechanical problem that kept them from completely doing one leg of the Problem. I recommend asking the team, “What would you do if some part of your vehicle did not work during performance?” Or what is your plan if something goes wrong? Do you move on to the next part of the script or stay in the same place and try to fix it? This is just like real life. Things don’t go as planned all the time, and you need to plan for things breaking.

9:32: Clarifications

My last general comment is about clarifications. This may seem repetitive. I will go over this later. But it’s so important I have to repeat it.

Do not forget to use private clarifications. Private clarifications are critical to Problem #1, to keep from making a mistake. Also, keep looking for public clarifications well after submitting the last final private clarification. There is a section on the Odyssey of Mind website all about clarifications. It is good to read. This is the end of the section on how to read the Problem #1 Problem description.

10:08: Program Guide

I’ll now move on to the Program Guide. The first section of the Program Guide is called “Over the limit.” In Over the limit, Problem #1 is always is the first type of problem. It is limited to eight minutes. The judges will ignore anything presented after eight minutes. I would recommend asking the team what they plan to do to stay within eight minutes.

The next key section is the checklist for completing the Long-Term Problem. It’s important to read the Problem carefully and make sure the judges see the objective items. They also must create and bring with them the forms on this checklist. Our judges are volunteers, and the fact is that your team will need to find volunteers to be judges.

Teams can be judged based only on what the judges can see. These forms are carefully studied by the judges before the team performs their solution. If the forms are missing or poorly put together, then your team will be working at a disadvantage. The biggest mistake is leaving them at home. Ask the team, “What can the team do to make sure that they are, that the forms are complete and brought to the tournament?”

Another mistake is a team reformatting the form, this is not allowed. The team is responsible for filling out the form. The words must be the team’s.

The next section is the “Role of the coach” section. Since Problem #1 is a technical problem, it’s very unusual for the team to have all the skills necessary. As a coach, you can coordinate the teaching of skills. If your team wants to tie-dye, then the coach can find someone that can teach them how to tie-dye. The key is the line. No one, including the coach, may give the team ideas or assistance.

This can be difficult. Teens can get ideas from a wide range of sources. I recommend they view past solutions. Lots of them.

12:10: Forming a Team

Skipping down to the section, Forming a team, team members may be more comfortable with people with the same types of skills. Teams that like performance tend to be attracted to non-technical problems. Teams with technical bent are attracted to technical problems. The more creative solutions are formed with teams with a wide range of skills, some technical, some performance. In Problem #5, the wow factor may be to include a technical machine or something. In Problem #1, the wow factor is to include performance or style elements.

Under Forming a team, you will find advice in how to form a team. Forming a team is complex. Team members recruit other team members, parents know parents and recruit team members, but coaches play a key role in that they can help create team with range of skills.

If you end up with an all-technical team, you will be pleased to know that I’ve seen lots of technical teams develop very creative and effective performances. But as a coach, you may need to do a bit of coaching.

My advice to get the team, to think about the wow factor. If it’s a team with a technical bent, ask them, who’s going to design the skit, do the props, etc.? When rereading the Problem or working on the Problem, try to get the team to visualize the solution and encourage them to figure out what parts are the hardest to do and build small parts that demonstrate this solution. On some technical teams the hardest part may be the props or the script. On a performance-oriented team, it may be some mechanical pieces. Have them experiment with those early, and that may change their thinking.

13:50 Clarifications

This brings me back to the section on clarifications. English is a complex language; words have multiple meanings. People tend to read into the words what they want to read. Do not assume you understand the problem. Clarifications will help you ensure that you don’t have a problem during tournament.

The key thing is that the team-specific clarifications are private. What you ask will not be shared to the team. It is a two-way communication between the team and a team of judges that judge only Problem #1. I recommend you turn in your clarifications and answers with your forms so that the judges are aware of your answers.

My advice on asking for clarifications: Clarification can have a significant impact on the development of the solution. This may result in rethinking and maybe some reworking of your solution. Thus, it is good to get as much out of the question as possible. First, read the Problem and see if the answer is already there. Second, be detailed and concrete. Since private clarifications are private, no other team will see it. Teams can disclose the details of their solution. Remember, the team needs to ask the questions. The coach can send the clarifications in and get the response, but the team should formulate the question.

15:11: Key Rules for Problem #1

The next thing I want to do in the Program Guide is go over the key rules for Problem #1. The coach’s job includes knowing all the rules, but these specific rules seem to be important to Problem #1.

Let’s start with Rule 10. What’s key here is that there are that all the parts of the problem must be able to fit through a doorway that measures 28” by 78”. I recommend the team even rehearse taking the stuff from check in to staging and out onto the floor. That way they can avoid issues like not knowing how to put the props back together.

The next rule is Rule 13. Here is where it says that forms may not be altered. This can only mess things up, not impress the judges.

Next rule is Rule 17. The following items are not allowed to be used in the team presentation of the solution.

- Lighter than air balloons that are not properly weighted down

- Items that are excessively hot or cold

- Items that leave residue — fire extinguishers, dry ice machines

- Internal combustion unions

- Flammable fuels

- Smoke bombs

- Fires in any form

- Liquids that can stain or cause damage to the floor

- Emergency response alerts

- Hover boards

Rule 20 reads about damage to the flooring. Teams must be careful not to cause damage to the competition site at any time. I’ve even seen the head judge stopping a team that was running a vehicle with a wheel that was jammed and drawing and scratching the floor. So be careful, and make sure that your vehicle will not damage the floor.

Finally, batteries. The rules about batteries are pretty straightforward. Basically, they are sealed and must be smaller than 15 inches when you weigh the high plus with plus depth. So, it’s a relatively small battery. A marine battery is probably the largest you can get away with. But definitely no car batteries.

The last area is on cost. This is a rather long section. Read it carefully. There’s lots of details here, but with Problem #1, there’s lots of opportunities to exceed the cost.

Also, these rules spell out how the team may use things that on their total value would be more expensive than the total, but they have a “for use” value. For example, you may buy a gallon of paint and only use a small quantity of it. Remember the only things that are costed are things that are shown during competition. So, if you buy something and don’t use it, that does not cost.

The final area to focus on is the glossary. When you read the Problem, you may notice that some of the words are in italics. These are glossary items. It’s common to misunderstand glossary items because Odyssey has a unique definition. With Problem #1, some glossary items are more understood than others. Second, the Problem may have a Problem-specific glossary. So, when you see a word that’s in italics in the Problem, first, look in the back of the Problem to see if that item is listed in a glossary there, and then check the program guide.

18:50: Boundary Lines

The Guide is an online guide, so you can actually search it for the glossary terms. There are three glossary items in the Program Guide relative to boundary lines, breaking the plane and areas that relate to each other and all are very critical in Problem #1, mostly because the, the vehicle’s traveling and we’re checking to see if things have crossed the line or are inside of a box. So let me go over these carefully.

First, is the glossary item for boundary lines. Boundary lines are considered on a vertical plane. So let me pretend that this is the boundary line here. So, if the vehicle, this is your boundary line. If the vehicle crosses this line at any point, even up here, this line goes all the way to the ceiling. It’s a sort of a vertical plane. So, you cross the line. It does not have to be the wheels across the line. It could be the front edge or the back edge or the corner of the vehicle that crosses the line. Sometimes this is a great advantage to the team because they don’t have to go all the way. Sometimes this is a big constraint.

The other definition that is right below the boundary lines is “Breaking the plane.” It states going beyond, but staying within the, the endpoints of an imaginary vertical plane, for example, a boundary or start line or a finish line. So, these planes could have an endpoint and you could just clip the end of it. And that would be considered breaking the plane, and it could be clipped with any part of the vehicle, not the wheels.

The third part, part of this boundary lines thing is this section on “Completely (entirely) within an area.” Again, a vehicle may be in a box and there may be a line around the outside of the box that extends to the ceiling. Any part of that vehicle that breaks the plane of that box, standing to the ceiling would be outside of that area.

And so, people think in terms of wheels being inside the box, but the vehicle may be outside of, or the vehicle may be too big to fit in. That would be not completely fitting into the area.

21:10: Character and Human Character

Another area people get confused in problem one maybe because the kids are more technical is the word “character.” Please read this carefully. There are two lines here. There are “character” and “human character.” You notice that a character does not necessarily need to be portrayed by a team member. You can have a puppet or something like that. Those are characters, but they must demonstrate some human characteristics

Human character, which is further down here, is specifically a human being and he is playing the character. So, there are more constraints about the character quality. If it says character, look to see if it’s saying human character.

Another one that people in Problem #1 get confused by, and maybe because it’s a technical problem and manufactured parts are commonly used, is the comment of “Commercially produced parts.” Now commercially produced means pre-manufactured not team-created, but when it says commercially produced parts, that would mean that you can’t use a whole car, but you can use parts of the car. Maybe, you know the car, some part of the car in some part of an airplane, you put them together to make a whole unique car plane thing. That would be allowed. But you can’t just have a car. You can’t just buy a kit that makes a car because that would be commercially and produced pre-manufactured but not parts.

22:44: Effectiveness

The next glossary item that people get confused by is the concept of Effectiveness in the performance. And it, we sort of spend a lot of time talking about creativity and engineering, but effectiveness is a funny sort of phrase, and it, it has to do with how the thing that’s being talked about being effective fits into the overall performance — how it adds to the story, the skit, the structure of the Problem.

The final glossary item I want to go over is the term “touching.” This is another one that people are confused by. The most common thing is they think that they put on a glove and push the thing they’re not touching it. Yes, they are. Or if they’re, if they have the shoe on and they’re pushing with their foot, they’re touching it. So touching is very important to consider. When it says you may not, no one may touch the thing, you must look at this glossary and see what they say to touch.

That ends a discussion of the Program Guide. Now I want to talk more generally about Problem 31. In general, coaches and parents can get in the way with their preconceived notions about technical problems. The number one piece of advice for coaches and parents is to let go and let their team members work the Problem. If you do, you’ll be amazed at what they come up with.

Adults have been conditioned to reject ideas, and team members may have picked up this bad habit. The key to Odyssey is not to reject ideas out of hand. Part of solving a problem is to try things. And if they don’t work, try something else. As a coach, you may reject an idea based upon your preconceived notions. You may even do this with subtle body language. Try to suppress this tendency.

24:31: Myths about Problem #1

I’ll try to cover the standard myths to get in the way in Problem #1.

The first myth: All vehicles must have wheels in a flat base.

Two: Mechanical items are only in Problem #2. You may have nonvehicle mechanical items in Problem #1.

Three: The vehicle must have a battery or be plugged in.

Four: Only middle school or older can build vehicles. This is not true. I’ve seen elementary schools build amazing vehicles.

When you do the Spontaneous Problems, you learn about the common concept of “common versus creative.” That also applies here in Long-Term. A car or a truck is the most common idea that comes to mind when you say the word vehicle. It’s not a creative solution.

There are lots of ways to enhance this common idea. You can change the wheels, change the shape, and change the location of the wheels. You can have a different number of wheels. You don’t even have to have wheels at all. The point is do not let your preconceived notion stop you. It’s important not to reject ideas immediately.

As a coach, you should use a large pad of paper and colored pens to get your team to throw out, and brainstorm as many ideas as they can. On Problem #1 this brainstorming is really critical. They will probably come up with many ideas that you’ll think can’t be done, but they will come up with solutions. After they throw these ideas out, run back through them and see how they can develop them. You’ll be surprised where they go. Do not let your ideas drive the team. Remember more creative, the solution, the higher the score.

26:20: Propulsion and Steering

The next thing I want to talk about is the confusing word “propulsion.” What’s confusing is that we think more about wheels or axles. Propulsion is about what converts in energy into motion. Again, what pops into your head? All the electric motors driven by a battery. This converts electrical energy from the battery or the power plant into motion. But there are many sources of power.

The simplest is human power. You can push a vehicle or sit on it and use your feet like in the Flintstones. Or you can have pedals, or push off the ground, or you can pull on a rope or a string. Even human power can be creative.

It can be air-powered — a fan on a vehicle or a fan blowing a vehicle. There are many types of propulsion. Don’t let your preconceived notions about what’s possible/not possible done. I’ve seen all of these work.

(27:29 Steering)

Another area where preconceived ideas get in the way is the term steering. Steering is a guidance system. What pops into the head is steering wheels in a car. But there are lots of ways to steer a vehicle that does not involve steering wheels. You can simply push to change directions. Could the Problem be solved with fixed steering, like always going in a straight line or always going in, in an arc? Maybe external steering, like tracks on a train, or things that the vehicle bumps against and changes direction.

The key here is not to let what immediately pops in your head become the solution. That’s probably the common solution, not very creative. This is a problem. Brainstorm first then work the ideas to see what can be done. In this process make sure to read the Problem and the Program Guide. In general, different forms of repulsion and steering are not allowed each year. And in the Program Guide, there’s a list of things that are disallowed all the time. In general, the Odyssey rule is: Anything goes except for what’s been disallowed.

28:45 Virtual Tournament

My final topic is the Virtual Tournament, or as some people call it the Online Tournament. This is an evolving process. So, you need to continue to check in.

Like the clarifications, it’s wise to have someone on the team look for stuff posted on the Odyssey of the Mind website and the Association websites about the Virtual Tournament. This page, the Virtual Tournament Procedures on the Odyssey of the Mind website is a great place to go. Treat this page as if you would treat the Program Guide. It’s full important information and rules.

So here a very important section is the required video. And it says that a submitted video can be 15 minutes long, but the performance is still eight minutes. Teams need to think about what to do for the remaining seven minutes.

My advice is treat this eight minute solution as a real life to performance. It starts and stops, and it can’t go over eight minutes. Seven minutes is the part of the performance where the judges come out and ask questions. When putting together the video, especially in Problem #1, a technical problem, there are a lot of objective elements. Remember the judge needs to see what’s going on so they can score it.

Show off the key details in the remaining time. Again, it’s a technical problem, and the judges can’t ask questions. Make the video a practice session, have the teams pretend to be judges and view it. Can they see the objective elements? Will someone else know what’s going on?

One big difference between the real-life performance and an online one is you don’t need a membership sign. I strongly recommend you name all your files that you submit with your membership number and name at the beginning. Judges may score a large number of competitions, and this will make sure that all your files make it to the judges.

Your solution is based on the Problem statement, creativity and how the video or paperwork is submitted.

Well, that wraps up the Problem #1 video. I hope to have helped you in your task as a coach to the problem 1 team. Please contact your Regional Problem Captain if you have any additional questions. If you have any suggestions about how to prove this video, please contact me through the Association.